Guest editor: Evelyn Wan

Deadline: CLOSED

Published: May/June 2022

In his One Year Performance 1980-1981 (Time Clock Piece), Tehching Hsieh imposes upon himself the task of clocking-in using punch-card technology every day, every hour, 24 hours a day, all through 365 days of the year. Forcing his corporeal self into the cold rigid regularity of mechanical clock time, he makes visible the rhythmic bind of the machine.

A by-now-classic performance piece, Hsieh’s durational performance aesthetically reveals technology’s intricate relationship to time and rhythm, and the potential violence of arranging our lives according to the clock and to the machine. The clocking-in mechanism is a mechanical algo-rhythm that shows the segmentation of time into hourly units, and an algo-rhythm that instigates a temporal logic upon which labour is quantified, managed, and compensated.

This call for paper is about algorithms and algo-rhythms, and our affective relationships to the algorithmic processes taking place in our mediated lives. While algorithms are often understood as techno-mathematical procedures executed by machines, algo-rhythms highlight the temporalities created by this process. Following Wolfgang Ernst’s media philosophy in Chronopoetics (2016), computers have their own internal clocking systems that allow for encoding/decoding processes to be synced, and for machine operations to run in connection with one another, as an internal rhythm emerges as part of this processing. These algorithms and algo-rhythms operate in the background much like the ticking of a clock, in our smartphone, on our apps, in the signal traffic of the internet… synchronising as devices communicate to each other, but many a time out of sync with our lived bodies.

How might we tune our senses to the architecture of algo-rhythms that seemingly eludes our conscious perception? How do artistic projects, through texture, sound, movement, and/or materiality, explore the rhythms, speeds, durations of digital culture? How do they reflect our affective relations to technology? Shintaro Miyazaki calls for an algorhythmic analysis, to focus on hearing, sensing, and playing with data structures, in order to understand the temporalities and rhythms created by algorithmic procedures. Together with Michael Chinen, Miyazaki turned sorting algorithms into visualisations and sound art, slowed down the techno-mathematical dimensions of signal processing into a phenomenological experience of sound, reminding viewers of the hidden rhythms of contemporary digital and data-based infrastructures.

AlgoRhythmic Sorting | Sorting Algorithms from Shintaro Miyazaki on Vimeo.

Shintaro Miyazaki and Michael Chinen, Algorhythmic Sorting (2012)

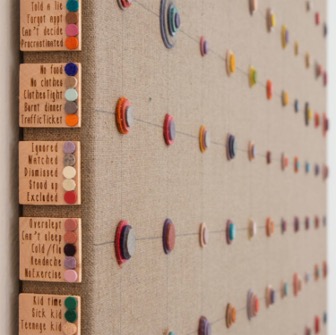

Data artist Laurie Frick, who uses self-tracking as her method, creates large-scale installations out of hand-built materials as datafied logs for activities like sleep and stress, and for time tracking for daily activities. The tactility of her artfully re-engineered datasets resensitises us to the scale of data trails captured by our devices and asks us to reimagine what images of the self could emerge out of such an obsessive and durational practice of bodily data collection.

Taking these artists as inspiration, this issue of Kunstlicht invites contributions that look at artistic explorations and embodied experience of technologies that structure and alter our experience of time in digital culture. We are interested in submissions that attenuate to interconnections between time, technology, body, and affect. Technology is understood here broadly in its material and immaterial, analogue and digital forms, and both historical and contemporary examples are welcome.

Evelyn Wan is Assistant Professor of Media, Arts, and Society at the Department of Media and Culture Studies at Utrecht University. She teaches cultural theory, philosophy of science, performance practices, and cultural research methodologies. Her work on the temporalities and politics of digital culture and algorithmic governance is interdisciplinary in nature, and straddles media and performance studies, gender and postcolonial theory, and legal and policy research.